NASA’s Europa Clipper mission to Jupiter gets support from Prague machine (Radio Prague International)

At the Jaroslav Heyrovský Institute of Physical Chemistry in Prague, scientists have created a unique device named Selina. It generates frozen nanoparticles that resemble those found around icy moons of Jupiter. The invention will support NASA’s Europa Clipper mission and help test spacecraft materials for future journeys into deep space.

Turning water into space-like particles

Selina is more than just a technical curiosity. It’s a tool that lets scientists generate streams of frozen water droplets and study how they behave under controlled conditions.

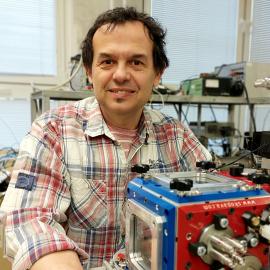

The man behind the demonstration is Ján Žabka, a researcher at the institute. He shows how water under high voltage can be turned into a shower of microscopic particles.

“We have water in these syringes. High voltage is applied there, it works like an atomizer. At the tip of the needle, the water breaks apart and forms tiny droplets. You see, each peak you notice, that is always the particle passing through the detector,” he explains.

Supporting NASA’s Europa Clipper mission

These artificial particles are very similar to the ice grains ejected from the surfaces of Jupiter’s moons. That is why Selina will be important for interpreting data from NASA’s upcoming Europa Clipper mission.

To highlight the scientific goals, Jordi Baumann from the University of Colorado adds:

“Small ice particles are released from the icy moons. We are interested in whether we can detect organic molecules in them. That can tell us whether there are suitable conditions for life, whether those moons are habitable.”

Testing spacecraft resilience on Earth

Because the spacecraft will only send back remote measurements, laboratory experiments on Earth are essential for comparison. Žabka and his colleagues use Selina to simulate exactly what might be found in space.

“You add various amino acids into the water, then look at what comes out. And later, when the analyzer measures something in space, the spectra can be compared. We know exactly what we have prepared – how big it is, what speed it has, and what charge. These are exactly the parameters we need,” Žabka says.

The device also serves another purpose: testing new space technology before it is launched. According to Žabka, Selina grew out of a practical need.

“We are developing a detector, an analyzer for space. And this was basically a way to test the analyzer before you send it out there – to find out what it can capture. We knew there are three accelerators in the world, but it’s not easy to get access to them. So we decided to build our own.”

Compared with large accelerators, Selina is much smaller, yet surprisingly versatile. Žabka uses a simple metaphor to describe it:

“It’s like a knife – with one simple tool you can cut wood or butter. With Selina you can insert a metal shaving about 100 nanometers in size, water containing organics, inorganics, biological material – or we can create our own nanoparticles from scratch.”

This flexibility also makes it useful for testing the resilience of spacecraft materials. By simulating the impact of micrometeorites, scientists can see how new surfaces will withstand conditions in orbit. “You see that micrometeorites really do make holes in the hull of the ISS. With our device we can generate similar particles and test new materials and their properties, so that such damage does not occur, or at least to make them more resistant,” Žabka notes.

Selina is not unique to Prague. Comparable instruments are now in use in Colorado and Leipzig, with the Czech-built version already playing an important role in preparing for the challenges of future space exploration.

prof. Abel Bernd Dr. rer. nat., DSc.

jh-inst.cas.cz

jh-inst.cas.czMgr. Žabka Ján CSc.

jh-inst.cas.cz

jh-inst.cas.czMgr. Spesyvyi Anatolii Ph.D.

jh-inst.cas.cz

jh-inst.cas.cz